This story comes to you from Sahan Journal, a nonprofit newsroom dedicated to covering Minnesota’s immigrants and communities of color. Sign up for Sahan’s free newsletter to receive stories in your inbox.

Minneapolis is creating a new climate action plan with ambitious goals to address pollution disparities that hit communities of color the hardest, but environmental justice advocates are criticizing a lack of dedicated funding.

A draft of the Minneapolis Climate and Equity Plan calls for large investments in insulating homes, lowering residential energy bills, cleaning up indoor and outdoor air, and increasing tree planting and green spaces. Many of those initiatives call for executing the work first in the cities’ Green Zones, areas in north and south Minneapolis with high levels of pollution and concentrations of people of color.

The plan, which also aims to lower carbon emissions, is supported by environmental justice organizations, but they want to see real money and clear timelines included. The Just Transition Coalition, a group of climate, labor, and immigrant advocacy organizations, held a June 7 rally calling for the city to raise $10 million in dedicated funding for the plan’s first year. The coalition includes MN350, Unidos, Service Employees International Union, and the faith group ISAIAH.

“Recent state and federal legislation has delivered massive investments in climate action, creating an opportunity to expand what is possible and position the city to lead at the speed and scale the climate crisis requires,” said MN350 Executive Director Tee McClenty. “Minneapolis has the opportunity to be a healthy, sustainable city that prioritizes the wellbeing of all residents no matter our race or income.”

Emphasizing equity

The Minneapolis Climate Equity Plan is an update of the city’s climate action plan, which originally passed in 2013. The older plan established the city’s Green Zones. But racial equity provisions in that plan were more of an afterthought, according to the city’s sustainability director, Kim Havey.

“With this plan, we really wanted to make it a forethought,” Havey said.

As a result, the city consulted several groups that work with immigrant communities and neighborhood councils in the most diverse parts of Minneapolis. The feedback they provided went directly into the plans, he said.

The draft plan focuses on 10 areas to create a more sustainable city. It includes calls for developing a clean energy workforce, recycling and composting 80 percent of waste by 2030, investing millions into weatherizing homes and buildings, and boosting public transit and improving pedestrian and bike infrastructure in order to reduce vehicle mileage.

The final version will include a year-long implantation plan, Havey said. There are provisions with immediate funding that can happen fast, he said, such as starting to weatherize homes and equipping aging housing stock with improved air filtration systems. Minneapolis has about $1.5 million from the federal COVID-19 response bill and block grants that it will spend on such work in the Green Zones, he said.

Their vision is to target blocks and multifamily buildings in the Green Zones that are known to be old and inefficient, and offering weatherization services such as better insulation and replacing old gas appliances for free or at very low cost. Residents who don’t want the improvements can opt out. This more systematic approach can provide real benefits fast, Havey said.

The city is already using some federal funds to boost tree planting on private property. There will also be immediate action on reducing plastic waste in restaurants by banning black plastic food containers and plastic straws and disposable silverware, which are all unrecyclable.

“I think you’re going to start seeing some significant changes,” Havey said.

Those changes will cost real money, he said. The city’s large weatherization proposal could cost as much as $1 billion, the Star Tribune reported in March.

Asking for funding, interpretation

Dozens of Minneapolis residents attended the city’s public health and safety committee meeting on June 7 to demand funding and stricter timelines for the plan. Among them was Lizete Vega Rodriguez, a resident of the Phillips neighborhood who immigrated from Mexico.

Vega Rodriguez wanted to testify to represent the Latino community. Most people like her are working during the day, and can’t attend an afternoon city meeting, she explained in Spanish, but they still care greatly about the climate.

“We are some of the most affected by environmental injustice,” Vega Rodriguez said.

Vega Rodriquez first got involved in the plan last year through her congregation at St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in Minneapolis. The city had interpreters during listening sessions with the south side Green Zone, and told attendees they’d publish the city’s climate plan in Spanish, Vega Rodriquez recalled.

Right now, the city’s 100-page draft plan includes a two-page summary translated into the Hmong, Oromo, Spanish, and Somali languages. Immigrant communities are impacted by high pollution levels, and deserve to read the full plan, Vega Rodriquez said.

Samarra Meek, with labor union SEIU 26, lived most of her life in north Minneapolis, and has asthma. She said when she moved a couple miles away to a neighborhood with better air quality, her symptoms improved. But moving shouldn’t be necessary, she said.

“I just want for our kids to have a better future,” she said.

Getting involved

Environmental group MN350 has its own vision, called The People’s Climate and Equity Plan, which began about five years ago among talks of a Green New Deal. The group partnered with other organizations to draft a local version for Minneapolis, according to senior organizer Ulla Nilsen.

MN350 says the time is ripe for the city to invest, with large amounts of funding becoming available through the federal government via laws like the Inflation Reduction Act, and from the state Legislature, which approved large climate and environmental justice packages. The group wants to see a permanent revenue stream established to fund climate justice and resiliency work.

“Minneapolis needs to fill in the gaps,” Nilsen said.

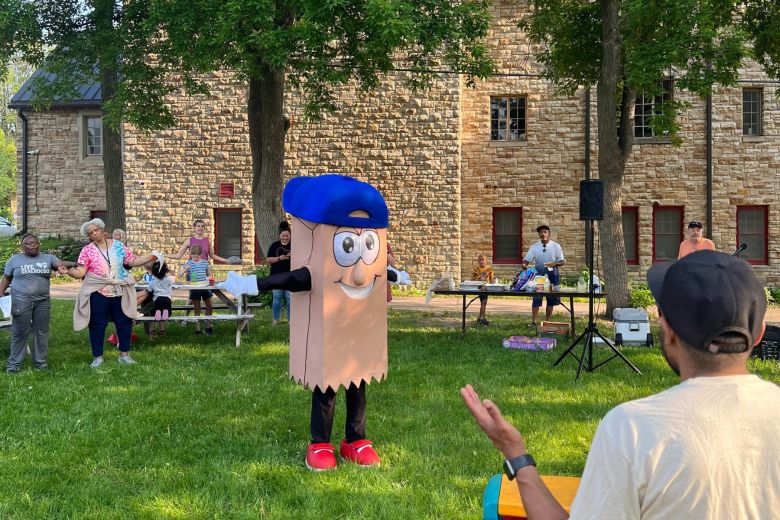

On a sunny Tuesday in late May, MN350 partnered on an event with Rusty and the Crew, a North Side nonprofit that works to help people recycle. They collected signatures for MN350’s petition to compel the city to support The People’s Climate and Equity Plan, and submitted public comments asking for dedicated funding.

Audua Pugh founded Rusty and the Crew in 2013 after becoming passionate about recycling organic and non-organic waste. The group sets up waste stations in family homes to help people recycle better. It’s one way every individual can make a difference, Pugh said.

Black communities on the North Side care about climate change, but often don’t have time to attend local meetings to get involved, she said. But they care when someone connects with them, she added, citing her experiences with her recycling outreach.

Reducing what goes in the trash helps improve local air quality by sending less waste to the Hennepin Energy Recovery Center (HERC), the county’s trash incinerator. Many see individual environmental issues as separate, but Pugh wants people to understand that they’re all connected.

“This is me trying to bring organizations together and trying to get environmental orgs in one place,” she said.

Candy Bakion signed the petition, and said she wants future generations to have better air quality.

“I want some green trees in my neighborhood, so that my energy bill will go down,” Bakion said.

Her three-bedroom home’s electrical bill can climb as high as $300 per month, Bakion said. She’s signed up for a community solar garden that was installed on North High School’s roof more than two years ago, but hasn’t been able to take advantage of it because she’s waiting for Xcel Energy to connect the array, which would allow it to produce electricity.

The city received more than 800 comments on the draft plan, Havey said. Most asked for more specifics about how the plan will be implemented, and more ways for individual residents to make a difference.

The Minneapolis City Council is expected to vote on a final version of the plan in August. The plan would be implemented over the next decade. Havey said there is implementation agenda for the first year.