Connecticut is about to adopt a new environmental justice mapping tool designed to infuse equity into policy-making and empower residents of overburdened communities in their efforts to prevent exposure to additional hazards and improve overall quality of life.

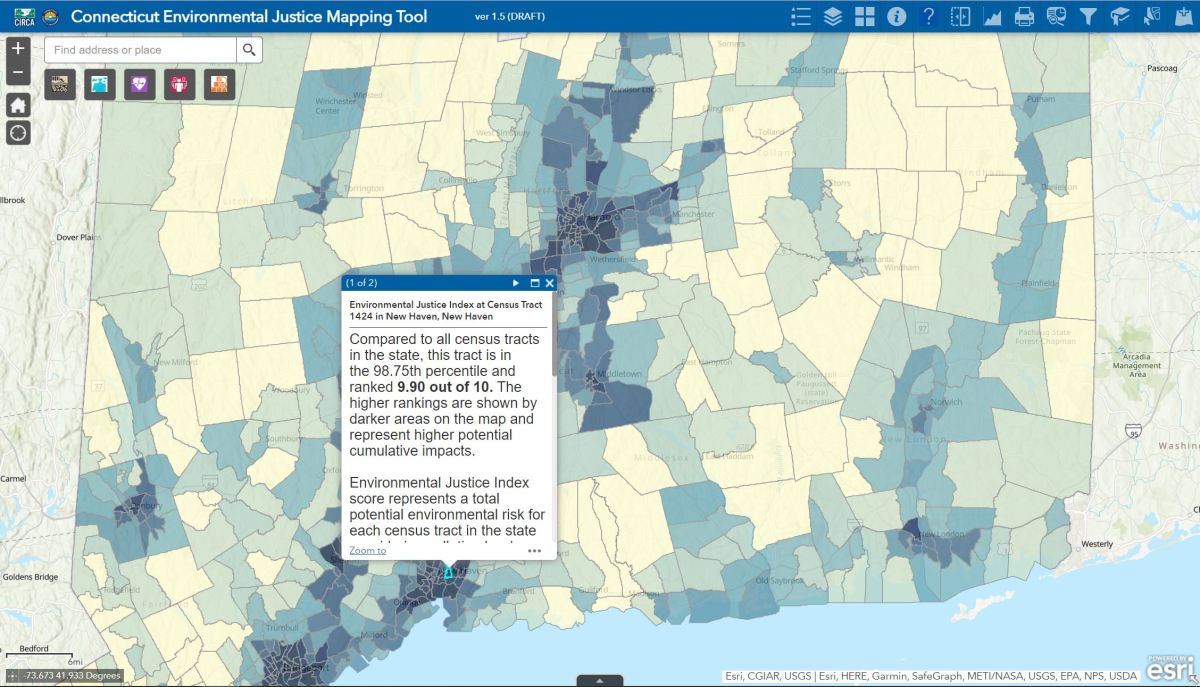

The mapping tool incorporates more than 50 different data sets to show which census tracts in the state are most at risk from pollution exposure, socioeconomic impacts and health disparities.

“It will show which areas are highly likely to be impacted for any kind of environmental justice,” said Yaprak Onat, assistant director of research at the Connecticut Institute for Resilience and Climate Adaptation at the University of Connecticut, which is developing the tool in partnership with the state Department of Energy and Environmental Protection.

“Environmental activists know the issues in their neighborhoods,” she said. “They can use this tool to say, ‘Hey, here’s the data to back it up.’”

On Monday, the development team opened a two-week public comment period on the tool with an online demonstration of its capabilities. People can try out the tool in English or Spanish on the institute’s website and submit feedback. The final version will be released next month.

The main map presents an environmental justice index for the entire state. Clicking on an individual tract gives its ranking between 1 and 10, with 10 being the most highly impacted based on the cumulative effect of a host of factors.

There are myriad options for diving more deeply into the data by breaking out the individual risk factors. For example, the tracts can be represented according to the potential sources of pollution within their boundaries, such as brownfield sites, Superfund sites and incinerators. Tracts with the highest potential for pollution show up darker in color.

Tracts can also be viewed according to their vulnerability related to socioeconomic factors, such as poverty and race/ethnicity, and health disparities, such as asthma rates and elevated lead levels.

The data used — much of it from state agencies — isn’t anything new, but only specific people know of each set’s existence, Onat noted.

“Now it’s going to be easily accessible so everybody can see the general picture,” she said.

Two years in the making, the tool came about through a recommendation contained in a 2021 report from the Governor’s Council on Climate Change. More specifically, the council’s Equity and Environmental Justice Working Group called for the development of the tool, which it said could be used in existing state programs, including the distribution of grant and bond funding.

It was developed incorporating input from residents of environmental justice communities at a half-dozen public forums in which attendees could try out the tool on iPads. The developers also consulted a Mapping Tool Advisory Committee composed of people and organizations active in environmental justice work.

At a May presentation of the tool to the Connecticut Equity and Environmental Justice Advisory Council, some environmental justice advocates expressed skepticism as to whether state agencies and lawmakers will actually incorporate the tool into their decision-making. Edith Pestana, administrator of the Department of Energy and Environmental Protection’s environmental justice program, responded that the tool wasn’t developed “to just sit on a shelf.”

“Hopefully,” she said, “this tool will make the case for legislators because they’ll have to see it. Some of them will type in their own neighborhoods and they’ll see they live in a dark blue area.”

Lynne Bonnett, a long-time environmental justice advocate who lives in New Haven, said the tool will be helpful, but only if it is used.

“It is on paper and remains to be seen whether EJ communities will continue to bear the brunt of regional infrastructures that create harmful conditions for their residents,” Bonnett said in an email.

The tool can work in conjunction with the state’s newly updated environmental justice law, said Alex Rodriguez, environmental justice specialist with Save the Sound. Rodriguez and other advocates lobbied hard for the measure, which finally passed on the last day of the most recent legislative session after its scope was reduced.

The law (Public Act 23-202) authorizes the Department of Energy and Environmental Protection and the Connecticut Siting Council to deny or place conditions on a permit for new polluting facilities in environmental justice communities if the cumulative environmental and health impacts there exceed a threshold higher than impacts borne by other communities.

The bill’s original language also applied that authority to permit applications for the expansion of existing facilities, but that language was removed, Rodriguez said.

“I think the tool is going to be needed for other policies as well,” he said. “It’s really going to force the state to look at the discrepancies in environmental protection across the state.”

At Monday’s presentation, Pestana said that once the institute hands off the finished tool to the department next month, an environmental analyst will be assigned to manage it and keep the data up to date.

“It is a living tool,” she said. “It is not stagnant.”