More than 100 years ago, an African American inventor named Alice H. Parker designed an indoor heating system using natural gas that she called a “heating furnace.” Her innovative design, awarded Patent Number 1,325,905 on December 23, 1919, was never placed into commercial production, but still stands as a groundbreaking advance in indoor comfort.

At this point in a conventional Black History Month profile, the narrative might turn to Parker’s life and the profound impact of her childhood curiosity on her later years. There would be at least one photo of Parker, perhaps in the process of drawing diagrams for her invention. The story would be a declaration of her achievement as an example of “Black girl magic.”

In fact, there is scant data of any kind on Alice Parker or her life. To be sure, an online search for Alice Parker reveals several profiles and tributes. The problem is that a lot of the content in these pieces is questionable at best, however well-meaning their intent. Even the nature of her invention is often misinterpreted, with some sources claiming that she invented the indoor furnace — she did not — or that she was the first to design a natural gas heating system — also not true.

There doesn’t even seem to be a verifiable photo of her. One widely-distributed photo that accompanies several pieces about Parker is actually a White woman born five years after the patent was granted.

“It’s consistent with things that I’ve certainly learned about and read about as it leads to record-keeping of Black history in this country, when we think about who gets to tell the story — who gets to tell history,” said Dr. Rabiah Mayas of the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago. “And when people are not allowed the power to tell their own histories, to document their own legacies, we know that there are huge gaps in what any of us have access to.”

As a Black woman who lived and worked prior to the modern Civil Rights movement and before women obtained the right to vote, Alice Parker represents yet another “hidden figure” in the sciences like NASA mathematician Katherine Johnson and others. Her absence as a more prominent presence speaks to the ongoing need to address the obstacles that perpetuate the lack of women and people of color in the sciences, Dr. Mayas said.

“It’s something I would love to learn more about in particular and in Miss Parker’s story, to understand what some of those challenges were,” Dr. Mayas said. “And really, have we really moved the needle? Because representation is incredibly important. Diversity is incredibly important. We have more women [and] we have more people of color in the sciences, but we also know that we still are not fully represented in terms of our numbers in the population.”

Photos and other images

In a tribute piece to Alice Parker posted in November, writer Melissa Gouty casts doubt on the commonly used photo of Parker, noting that it “seems to be a white woman in clothing more suggestive of the 1940s or 1950s” and is “clearly a different person.”

While many Black people have fair complexions and features that can appear racially ambiguous, Gouty is right. The photo is the wrong Alice Parker.

A major clue to the true identity of the woman mistakenly identified as Parker the inventor can be found in the caption included with a profile for NJ.com, which credits “lyons-family.co.uk” for the image. The website is a family genealogy portal, and reveals the Alice Parker in the image was born in London in 1924 — five years after the furnace patent. Further confirming Gouty’s suspicions, the genealogy site estimates the photo was taken in 1942.

The genealogy website is an absolute treasure trove overflowing with photos, family trees and narratives about various members of the extended Lyons family. This wealth of data stands in marked contrast — and irony — to the nearly total absence of any information about the African American Alice Parker and her life experiences.

It is not clear who originally misattributed the photo, but it appears in a multitude of articles about Alice Parker the inventor. One rendering of the image shows her with a markedly darker complexion than the woman in the original photo. Another illustration of Parker on the children’s site Nickelodeon alters her image to erase her smile, in addition to displaying a darker skin tone.

Gouty also noted that other profiles of Parker show an entirely different photo of another Black woman, also with a much darker complexion. This second photo has also been identified as either Marie Van Brittan Brown, born in 1922, or Bessie Blount Griffin, born in 1914. In either event, these two African American inventors were both born much too late to have obtained a patent in 1919.

Parker’s birthplace and residence

The furnace patent is credited to “Alice H. Parker of Morristown, New Jersey.” Beyond that, details are scarce about where and when Parker may have lived.

According to a profile on the National Society of Black Physicists website, Parker was born in 1895 in Morristown, New Jersey. Another profile on the New Jersey Chamber of Commerce website also states that Parker was born in Morristown “shortly after the Civil War,” which ended in 1865.

A number of sources state that Parker died in 1920 at age 24 or 25. However, January 1920 Census records obtained from the North Jersey History and Genealogy Center include a woman named Alice Parker listed as a 35-year-old cook — which would place her year of birth as approximately 1885. The record also states that this Alice Parker was born in Virginia and married to a 45-year-old butler named Edward whose birthplace is listed as Canada.

Alice and Edward Parker from the 1920 census records were listed as Black domestic employees of a White man named George Fanning whose 60-acre farm was located in Boonton, just outside of Morristown, the county seat.

Although there is no definitive proof, it’s very possible that the Alice Parker from the 1920 New Jersey census records is also the Alice H. Parker who obtained the “heating furnace” patent in 1919, despite the discrepancies between various accounts.

As a cook living in a large house, Parker would have had ample motivation to design a multi-room furnace. Indeed, Parker’s profile on the New Jersey Chamber of Commerce website stated that a desire to keep warm in her home during cold New Jersey winters inspired the design for her “heating furnace.”

Parker’s educational background

The earliest known media mention of Parker’s patent appears in the February 1920 issue of The Crisis, the official publication of the NAACP. A roundup of notable accomplishments by African Americans called “the Horizon” includes the text: “Alice H. Parker, a graduate of Howard University, has been issued a United States patent for a heating furnace.” The same blurb was reprinted in a similar roundup called “The Colored Citizen” in the March 13, 1920, edition of Cayton’s Weekly, an African American publication based in Seattle published from 1916 to 1921.

The process for filing a patent application is rigorous and demanding, with many potential pitfalls. The patent’s clear explanation of the design, along with its well-executed drawings, suggest that the Alice H. Parker who submitted the sophisticated patent application for her “heating furnace” was educated as well as highly intelligent.

However, according to the Howard University alumni office, the only matching record was for an Alice Parker who graduated in 1939, almost certainly too late to have obtained a patent in 1919.

Another commonly cited source is a 1910 commencement program from Howard University Academy, a high school program affiliated with the university, that lists an Alice H. Parker from Clifton, Virginia, among its graduates.

But while they’re both identified as being born in Virginia, the Alice Parker in the New Jersey Census record would have been 25 years old in 1910, when the Alice H. Parker at Howard University Academy was graduating. If the National Society of Black Physicists’ 1895 birthdate is correct, Alice Parker would have been 15 at the time of the 1910 commencement.

However, the Alice Parker in the New Jersey Census record was married, and would likely have attended school under her birth name. A request to the Howard University alumni office for a listing of students named “Alice” during the relevant time period was declined, citing confidentiality.

So it’s possible that the Alice H. Parker from Howard University Academy is the inventor. It’s also possible that the Alice Parker working as a cook in New Jersey is the inventor, and attended Howard University under an unknown birth name. But it’s unlikely that both of these scenarios are true at the same time.

Parker’s ‘heating furnace’

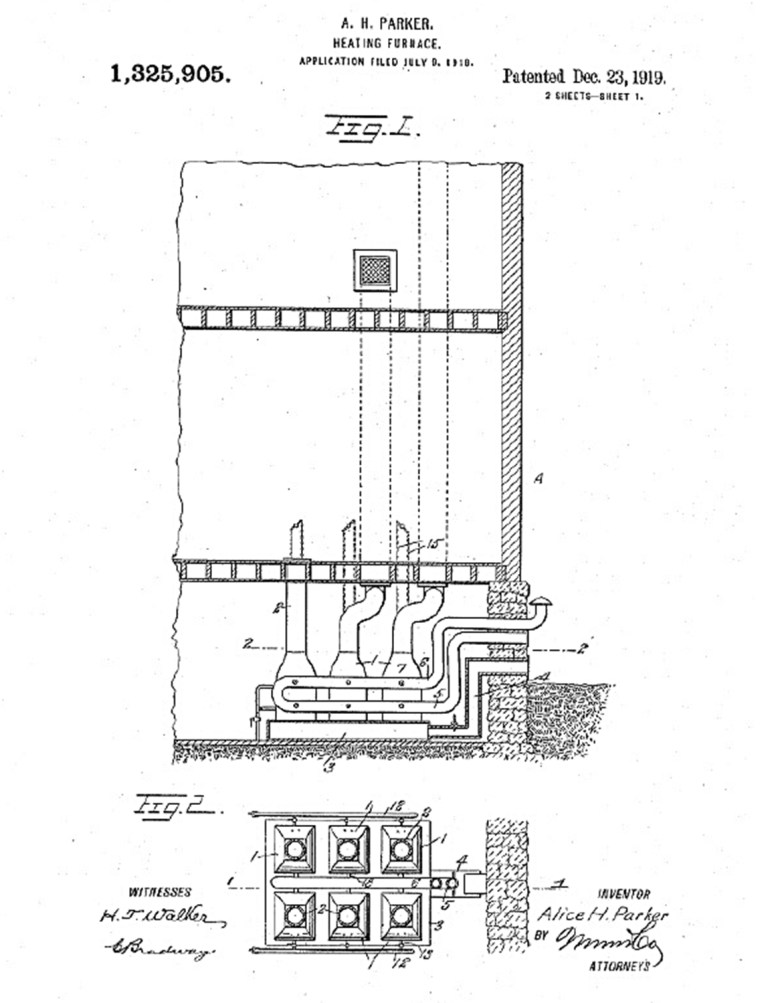

Alice Parker’s “heating furnace” was essentially a rudimentary heat exchanger, comprised of a series of separate mini-furnaces. Each mini-furnace would be connected to a common air exchanger that created hot air from the combustion of natural gas, which would then be directed through ductwork throughout the entire house. While natural gas was already in use for industrial heating applications, and for lighting during this period, Parker’s central heating furnace design is credited as the first to use natural gas for heating homes and offices.

During the early years of the 20th century, wood-burning fireplaces or coal-burning stoves were the primary means of indoor heating. Heating with natural gas produced none of the smoke, soot and ash associated with burning coal or wood indoors. Using natural gas as a heating source also eliminated the need to restoke a fireplace with wood or a free-standing stove with coal — along with vastly reducing the risk of a fire from an unattended heat source.

While Parker obtained the services of an attorney to file her patent — as listed on her application — she deserves credit for navigating the complex patent application process, perhaps largely on her own.

“I can’t imagine the process of filing for a patent during that time and being one of the only [Black inventors] at the time and not having a community, not having mentors who perhaps had traveled the same path and could support and nurture along that path,” Dr. Mayas said.

Innovation and inequity

Parker’s groundbreaking whole house heat distribution system was much more efficient than either coal-burning stoves or fireplaces. And while natural gas is no longer a novelty as a heating source, Parker’s innovation fundamentally changed how indoor heating systems operate by being the first to incorporate separate, individually controlled heating elements in each room. Room level temperature controls in Parker’s “heating furnace” adapt seamlessly with modern smart home technology, which is projected to be used in more than 60% of all U.S. homes by 2026.

Yet, unlike Carrier Corporation or Lennox International Inc., there is no heating and cooling company named after Alice Parker. Except for her patent application, there seems to be no evidence that she engaged in structured scientific research. It’s a reasonable conjecture that the fact that Alice Parker was a Black woman during the early 1900s truncated her opportunities, including a potential career in the sciences, Dr. Mayas said.

“This was a time where not only could Black women not vote but White women could not vote at the time. So, we’re not seen as voting citizens of this country. There were still many institutions of higher education that were not permitting [Black students to attend], whether that was by their policy or by their practice. They were not admitting Black students, African American students into their programs,” Dr. Mayas said. “[Scientific research] was designed largely for White males, to be honest. That is, the scientific enterprise, as well as higher education, was really originally structured around men.”

Recognition and inspiration

Despite the fact that so little can be confirmed about Alice Parker and her life, she has not gone completely without well-deserved recognition. In 2019, the National Society of Black Physicists honored Parker, stating that her revolutionary invention “conserved energy and paved the way for the central heating systems we all have in our homes today.”

Likewise, in claiming her as a native resident, the New Jersey Chamber of Commerce established the Alice H. Parker Women Leaders in Innovation Awards in 2019 to honor women who utilize innovation to improve life in the state. The New Jersey Chamber of Commerce made an extensive effort to obtain background information about Parker in the process of creating their profile and award, and shared those findings with the Energy News Network.

Aside from this type of official recognition, seeing others who look like them in science and technology careers is important for Black girls and young Black women. It’s a signal that the sciences are open to them — not as an extraordinary achievement, but as a conventional career path — as it was for Dr. Mayas.

“The [first] laboratory in which I worked was run by a woman named Dr. Audrey Trotman who was a Black woman who was married and had children and was a successful researcher and professor,” Dr. Mayas said. “And I think because that was my first research experience and that it wasn’t called out as particularly special, it was normalized. It was a normal experience to have a Black woman running the lab and doing this incredible research. I think it was incredibly impactful because I didn’t have an experience where that was not normal.

“I had the privilege of seeing as my first mentor in the sciences someone who looked like me, sounded like me, had cultural connections to me. And so, I think a lot about that as an adult about how meaningful that was and how important it is for all of our young people to have some of that experience and representation be normalized. Not celebrated as an exception, but part of their normal engagement with science.”